📘 CIVICS FOR THE BEWILDERED

A Vintage Guide to a Republic with Cracks in Its Foundation From The Twainian Civics Triptych: Power, Conscience, and the Lost Arts of Citizenship by Kimberly Twain

PREFACE

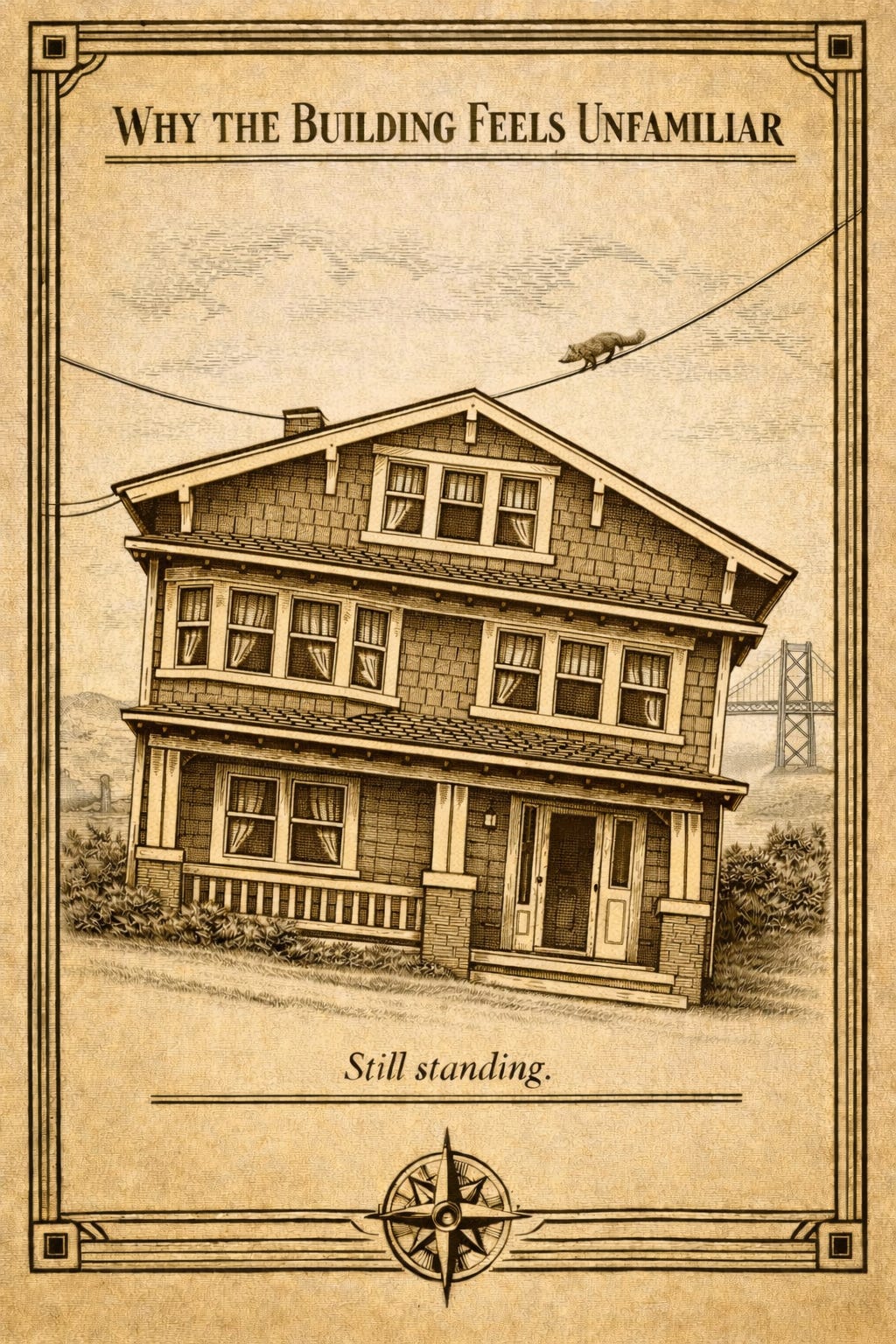

Why the Building Feels Unfamiliar

Civics, as it turns out, is a lot like my house.

I live in Crockett in a 1912 Craftsman that has seen better carpenters and, if we’re honest, better centuries. It sits across the street from the former home of John Muir’s father-in-law, which stands upright with the composure of a man who still reads the paper at breakfast. My house stands too, but with more personality than posture.

The front steps lean decisively to the right. Not politically. Structurally.

Doors open when they feel like it.

The ground has begun a slow and thoughtful migration toward the neighbor’s 1894 place.

The squirrels have unionized in the scuppers.

One of them, Twitcy, greets me every morning as I sit on the porch with coffee and look out at the rolling green hills. From the bedroom window we watch ships move through the strait and squirrels crack walnuts on the roof like tiny percussionists with no respect for sleeping hours. We watch them. They watch us. We have reached an understanding that is not, strictly speaking, in writing.

And yet we love this house.

The lines are good.

The bones are old growth.

The bay windows run floor to ceiling.

From one room we see cows grazing on a green hillside. From another we look across to the Stetzel house and the history of Valona. Every home on this street is from the same period. They are all still here. Weathered. Slightly crooked. Entirely alive.

But after ten years inside this structure, I know something is off.

Two outbuildings on the property have already surrendered to gravity and memory. An ivy-covered cottage lost its chimney in a winter storm and now hosts a raccoon family. The mother limps. We call her Limpy, though she has never introduced herself formally. An old stable where work horses once hauled goods up the hill is collapsing board by board. I watch it from the kitchen window while making toast and think, not about raccoons or horses, but about the United States government.

This is not as strange as it sounds.

Most Americans sense that something is wrong with their government but cannot quite name what it is. They feel it the way one feels a draft in an old house. The windows look fine. The walls appear upright. The roof has not yet departed. And yet something rattles. Something shifts. Something no longer fits the way it once did.

The usual explanation is that citizens have stopped caring about democracy.

I suspect the opposite.

I suspect they were never handed the floor plan.

Civics was once the practical knowledge required to live inside a republic without setting it on fire accidentally. Not patriotism. Not enthusiasm. Not a collection of decorative dates. Just the basics. Who holds power. Who limits it. Where it begins. Where it is supposed to end. And what the rest of us are meant to do when it wanders off unsupervised.

Over time, civics was trimmed down to trivia. A branch here. A slogan there. A respectful nod to a flag somewhere in the background. The structure itself became decorative, like those classical columns added to modern buildings that hold up absolutely nothing but still look reassuring in photographs.

Meanwhile, the building kept changing.

New wiring appeared. Old load-bearing beams were quietly removed. Side doors became main entrances. Entire rooms were repurposed without telling the tenants. Citizens were informed, politely, that the renovations were complex and best left to professionals.

This book is not interested in how government feels.

It is interested in how it is built.

It is for anyone who suspects that power has grown louder, less accountable, and more abstract and would like to know where the beams actually are. Which walls are structural. Which are decorative. Which cracks are cosmetic. Which ones mean you should probably call someone before the ceiling joins you for dinner.

You do not need to love politics to read this book.

You only need to live here.

Because a republic, like an old house, can stand for a very long time while quietly coming apart.

And because before anything can be repaired, someone has to walk through the place with the lights on and admit, kindly but plainly, where the floor has started to slope.

Consider this book that walk-through.