📚 Freedom Schools and the Education That Refused to Disappear

🧭 The Family Curriculum

I come from a long line of educators.

In our family, teaching was not a profession. It was a survival system. Near the turn of the twentieth century, my great-grandmother opened the first school for Black children in our small Louisiana town. My great-grandfather taught too. Family lore says he rode from place to place on horseback, carrying lessons across fields and dirt roads, teaching wherever children could gather. He did this at risk to his life. Education for Black people in the American South was not considered a neutral activity. It was considered a threat.

So education became our inheritance.

Black history was drilled into me at the dinner table and in living rooms long before I saw any of it in a textbook. My Aunt Julia Mae, herself a teacher, gave me a book of poetry by Paul Laurence Dunbar that I still keep. I attended segregated schools in the South, yet those schools bore the name of a relative. Inside those walls, we never felt lesser. Still, there was a quiet confusion. Why were we learning so much history at home that never appeared in our official curriculum? Why did the public textbooks suggest that my people entered the story only as enslaved labor and then slipped back into the margins?

As a child, I felt the unease of that absence. I sensed a limit on where I could move and what I could imagine. I worried that my people had done nothing but endure. Then my family handed me a different archive. They taught me about Black poets, teachers, organizers, rebels, and builders. They themselves marched with Dr. Martin Luther King. They told stories not printed in the schoolbooks we were issued. They placed art books and literature by Black writers and artists in my hands. We studied music and learned of Black musicians who forged their own paths despite the working conditions imposed by Jim Crow. They filled in the missing architecture of the past. The effect was structural. I did not feel erased, because they would not allow it.

For years, I wondered why I had received this parallel education, this quiet supplemental syllabus passed down through family memory.

Recently, I found one of its sources.

Freedom Schools.

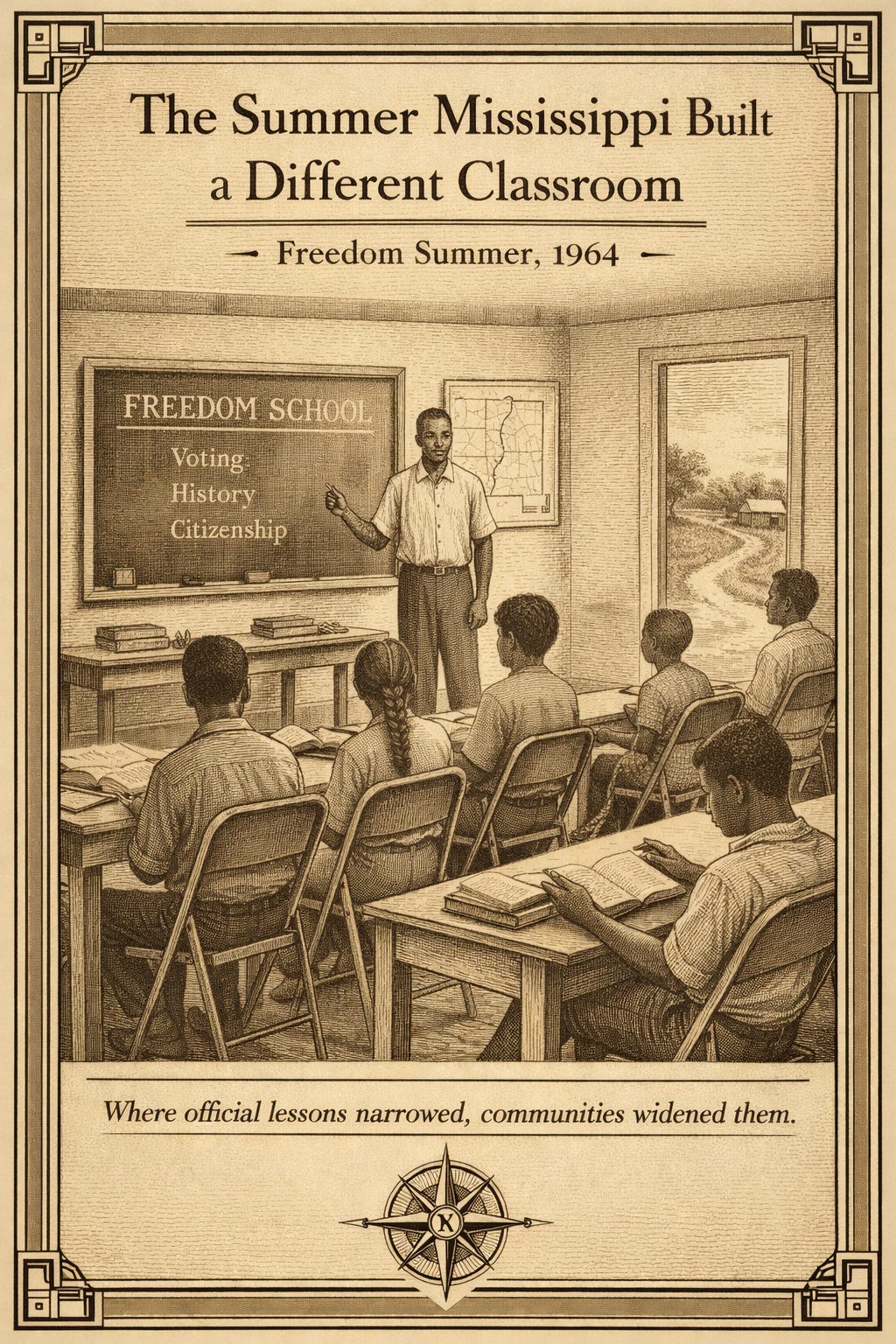

🏫 The Summer Mississippi Built a Different Classroom

In 1964, during Freedom Summer, activists and local communities in Mississippi created a network of temporary schools for Black children and teenagers. The official school system in the state was segregated, underfunded for Black students, and tightly controlled in what it allowed them to learn about themselves and their rights. Many Black students attended schools that avoided or distorted Black history, civic participation, and the mechanics of voting.

The Freedom Schools were built to correct that omission.

They operated in churches, community centers, and borrowed rooms. Volunteer teachers and local leaders created a curriculum that centered Black history, constitutional rights, literature, and civic engagement. Students studied not only what democracy claimed to be but how it functioned in practice. They read, wrote, debated, and organized. They learned how to register to vote, how to speak publicly, and how to analyze the structures shaping their lives.

The goal was not remedial education.

The goal was civic presence.

Young people were encouraged to ask questions about power and belonging. They wrote essays about their communities and their futures. At the end of that summer, many students helped draft a document often referred to as the Declaration of Independence of the Negro People of Mississippi, a statement written by teenagers assessing the democracy around them and demanding fuller participation within it.

The schools lasted only one summer in their original form. Their influence did not end there.

🔥 A Lineage of Hidden Classrooms

The Freedom Schools did not appear out of nowhere. They emerged from a longer tradition of Black communities building their own educational systems when official ones excluded or diminished them. During slavery, people learned to read in secret. After the Civil War, Reconstruction-era schools were built by newly freed communities and often targeted for destruction. In the twentieth century, educators across the South and beyond carried knowledge from place to place, sometimes literally on horseback.

By 1964, the Freedom Schools became a visible expression of a long-standing practice: when formal curricula erase you, you build a supplemental one.

Their legacy can be traced through community-run schools, liberation schools, Black Panther educational programs, ethnic studies movements, and ongoing debates over whose history belongs in public classrooms. They were temporary structures with permanent consequences.

📍 The Secret Was Never Only Ours

Looking back, I understand that the education my family gave me was not unusual. It was part of a wider tradition. Many Black families maintained a parallel curriculum at home, teaching history, literature, and civic awareness absent from official textbooks. It was not secrecy for secrecy’s sake. It was continuity.

My great-grandparents riding out to teach.

My relatives naming schools.

My family reciting history at home.

Mississippi building Freedom Schools in 1964.

These are all variations on the same blueprint.

When a system narrows the story, people widen it. When textbooks omit, communities annotate. When official classrooms cannot hold the full record, someone opens another room.

🪑 The Desk That Travels

Freedom Schools remind us that education is not confined to buildings or districts. It is a civic inheritance carried by families, communities, and teachers who refuse disappearance. Their classrooms may be temporary. Their lessons tend to travel.

I used to wonder why my family gave me a history lesson that felt almost like a secret.

It was not a secret.

It was a continuation.

Next installment:

From Freedom Schools to the Black Panthers