The Closing of Legacy

When institutions abandon art and women’s intellectual life, they do not become efficient — they become naïve, and inquiry itself begins to narrow.

The closing of a college is often described as a financial event. A balance-sheet failure. A market correction.

But when the institutions unraveling are more than a century old, central to women’s education, and built explicitly to house serious arts education, what is being dismantled is not simply an organization, but a philosophy.

Quietly, almost politely, the Bay Area has begun to dismantle the architecture that once sustained artists’ artistic and intellectual lives, particularly those built to protect women’s access to serious education. Much of that architecture existed to treat the arts as a rigorous, lifelong pursuit — not as enrichment, but as vocation.

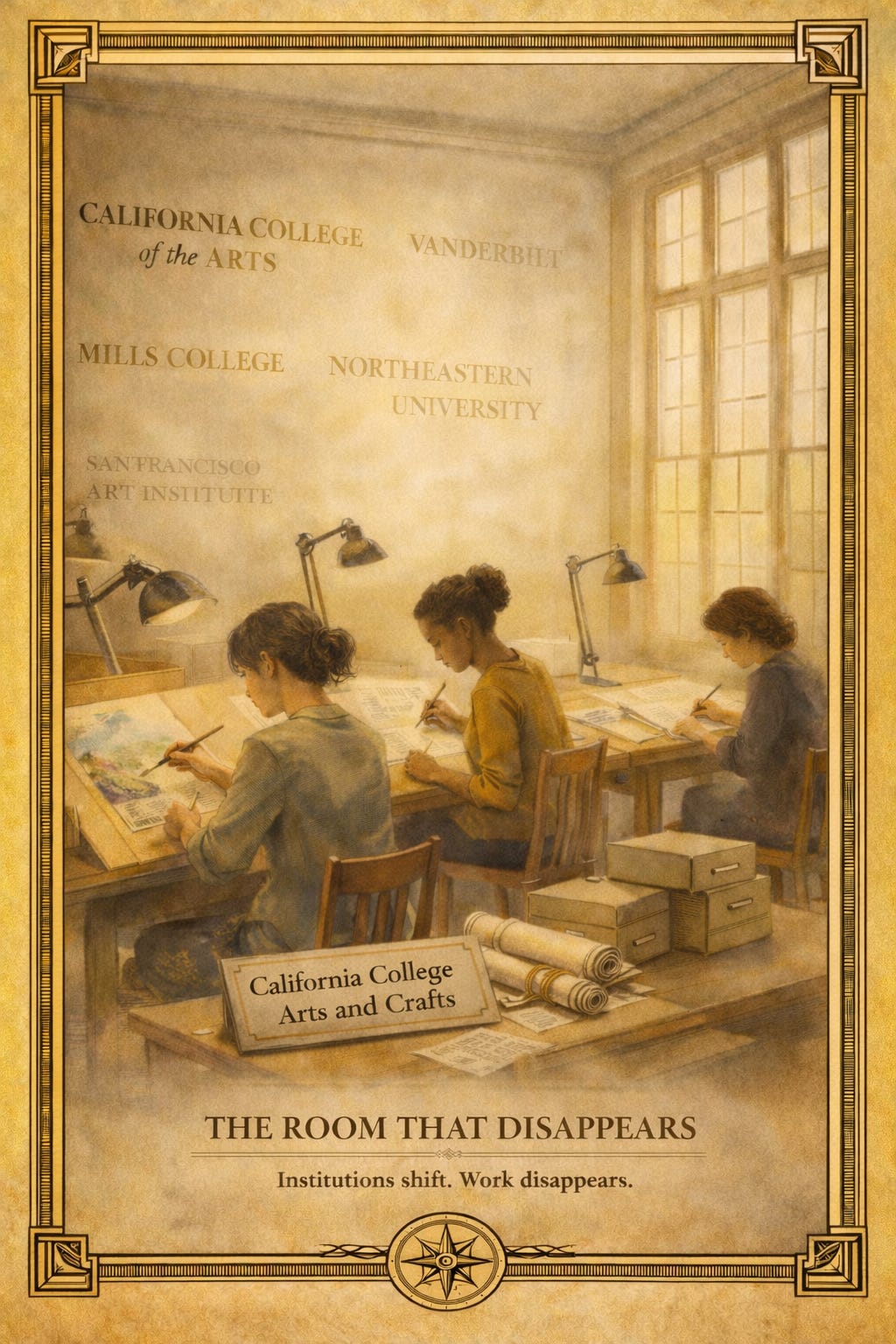

California College of the Arts, founded in 1907 as the California College of Arts and Crafts, has announced it will conclude operations at the end of the 2026–27 academic year, with its San Francisco campus transitioning to Vanderbilt University. Mills College ceased to exist as an independent women’s college when it merged into Northeastern University in 2022. And the San Francisco Art Institute closed in 2022, entering Chapter 7 bankruptcy the following year.

Each outcome differs in form. The result is the same.

Institutions that once treated the arts and women’s education as civic responsibilities are being absorbed, rebranded, or dissolved. What is lost is not only schools, but protected spaces where artists and students were encouraged to think critically, make courageously, and imagine alternatives to inherited systems.

Architecture as a Moral Statement

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, women’s education in California was not imagined as provisional. It was designed in stone, timber, and reinforced concrete, meant to last.

Few figures understood this better than Phoebe Apperson Hearst, one of the most consequential patrons of women’s education in American history. Hearst believed education was a public obligation and that architecture itself was a form of social policy. She funded institutions not to extract value, but to generate it across generations.

Her most enduring legacy may be her mentorship of Julia Morgan, the first woman licensed as an architect in California and one of the most prolific architects in American history.

Morgan did not design women’s educational spaces as diminished versions of men’s institutions, nor did she treat the arts as ornamental. She designed places where women — as artists and thinkers — could study, make, and work seriously, with the arts at the center of intellectual life rather than at its margins. Her buildings assumed continuity. They assumed women’s intellectual lives deserved permanence.

Architecture, in this context, was not decoration. It was a declaration.

Mills College: Six Buildings, One Integrated Vision

Founded in 1852, Mills College embodied that long view. Its campus was deliberately shaped over decades, including six major buildings designed by Julia Morgan, forming one of the most significant concentrations of her educational work.

These included El Campanil, whose survival of the 1906 earthquake helped establish Morgan’s reputation; the Margaret Carnegie Library; the Student Union; Kapiolani Cottage; the original gymnasium and pool; and Ming Quong, later renamed the Julia Morgan School for Girls. Together, these structures organized daily life: study, gathering, movement, and making.

At Mills, the arts were not extracurricular; they were structural, embedded in the daily rhythms of women’s intellectual life and open to artists and scholars more broadly. This was education understood as permanent civic infrastructure.

The merger that ended Mills’ independence did not erase these buildings. But without the institution they were designed to support, they risk becoming shells divorced from purpose, their meaning flattened into real estate.

That is not preservation.

It is hollowing.

From Fire to Continuity

My education at the California College of Arts and Crafts taught me how to question, disrupt, and act. Mills College taught me how to sustain that work over time.

Where CCAC was combustible, Mills was continuous. Where CCAC pushed outward, Mills held steady. Together, they formed a complete education in risk and responsibility, experimentation and endurance.

The loss of one would have been devastating.

The loss of both is a cultural severing.

Personal Witness: California College of Arts and Crafts

When I arrived at CCAC, it was an intact institution. Demanding. Serious. Alive with argument.

Craft mattered there. We fought to keep the “C” in the name because it stood for something older than branding: the belief that making was a form of thinking, and that the hand was an instrument of knowledge. For many of us — artists of all genders, and especially women — the arts were not a fallback but a way into authority, authorship, and professional life.

We argued over curriculum. We challenged language. We were taught to fail boldly, to think globally, and to understand architecture and art as ethical acts. The world came to us — not as spectacle, but as conversation.

Slowly, though, something shifted. Memory thinned. Language changed. Craft gave way to scale.

Then the “C” disappeared.

Now the institution itself is winding down, its campus transitioning to Vanderbilt.

Personal Witness: Mills College

I came to Mills at a moment when it still felt whole.

From the first Julia Morgan building at the gate, the campus announced itself as a place built for women’s seriousness. Later, as an MFA student, I was taught and mentored by women who treated writing as a long practice, not a commodity. We learned patience. Endurance. How to carry work across years.

I heard rumors of mismanagement at Mills and believed them. That explanation felt sufficient at the time.

Then the San Francisco Art Institute closed.

Then Mills lost its independence.

When CCA announced it would wind down entirely, I became alarmed. The sequence mattered. One institution could falter. Two, perhaps. Three, in quick succession, with different boards and leaders, began to look like something else.

Money, Management, and the Pattern

It would be dishonest to pretend that money and management had nothing to do with these closures. Of course they did. Decisions about tuition, enrollment, expansion, debt, and the quiet hope that real estate might someday rescue the balance sheet shaped what happened at CCA, Mills, and SFAI.

But taken one by one, those explanations feel plausible.

Taken together, they feel insufficient.

These were different institutions, with different leaders and internal cultures, yet they fell in sequence, one after another. It strains belief to conclude that all three simply made the same mistakes at the same time.

What begins to emerge instead is a larger shift in the ground beneath them.

These schools were built for a world in which the arts — particularly as a mode of women’s education — were treated as civic responsibilities, not consumer products. As higher education has been remade into a marketplace, institutions devoted to slowness, craft, and intellectual refuge have found themselves playing a game whose rules were never written for them.

Management mattered.

But the rules changed first.

What Should Happen Next

What should happen next is not another quiet transition or rebrand, but a reckoning.

Arts education — and the institutions that have historically protected women’s intellectual life within it — must be treated as civic infrastructure, not market experiments. That means public investment, philanthropic recommitment, and governance models that prioritize educational mission over scale, real estate, or brand expansion.

It also means pausing before assuming that consolidation equals preservation. A campus can survive on paper while its purpose quietly disappears.

If California wishes to remain a place where culture is produced rather than merely consumed, it must decide whether artists and thinkers are a public good — or an expendable luxury.

When Institutions Stop Teaching Courage

Institutions do not only transmit knowledge.

They transmit permission.

When institutions stop teaching courage, they transmit submission. Thinking becomes managerial, risk-averse, detached from the hand and the body.

I resist this deliberately. I slow down. I write by hand. I remember that the hand can still draw, sketch, and imagine directly from human thought.

This is not nostalgia.

It is cognition.

History shows what follows when art is marginalized and the feminine is suppressed. Societies describe it as efficiency or discipline. Creativity is tolerated only when it serves power. Education shifts from inquiry to compliance.

When artists lose access to serious arts education — and when women lose protected access to it altogether — society does not simply lose artists. It loses entire ways of thinking, questioning, and dissenting.

The Bay Area once built institutions that understood this danger. It built places where art mattered, where women’s intellectual lives were central, and where courage was taught through practice.

Those places are disappearing.

A society that stops teaching courage should not be surprised when imagination disappears and power goes unquestioned.

This is a great piece, Kimberly!

Such an important message, thank-you!

It's messed up, right?!! The Washington Post thing has me all in a tizzy. It's really crazy. Where are the journalists? I guess they are trembling in their boots. How did that happen?

Hello, my dear. I hope you are well. I'm thinking of making a trip up there soon. Hold on to my red chord!

Best,

kt