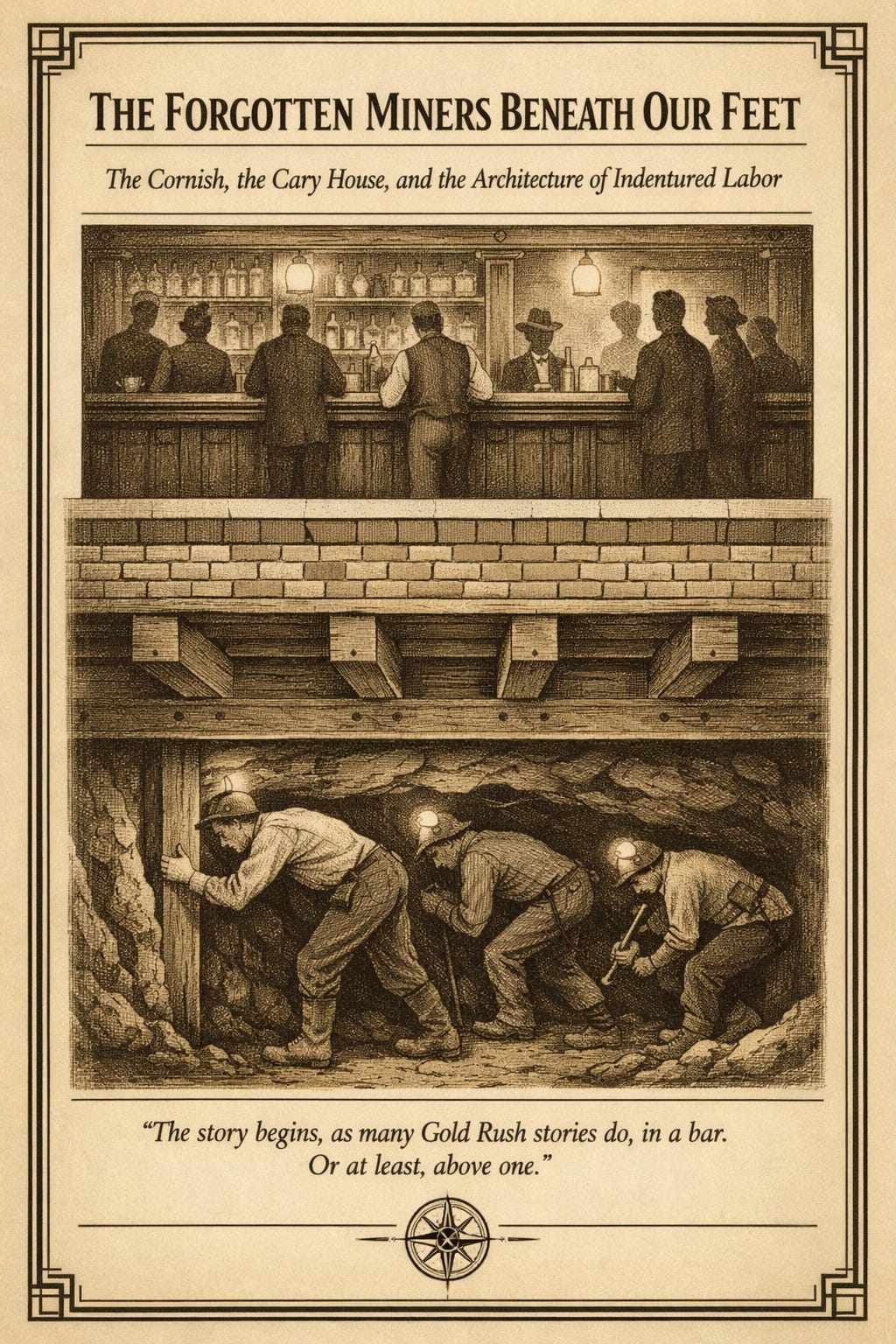

The Forgotten Miners Beneath Our Feet:

The Cornish, the Cary House, and the Architecture of Indentured Labor

The story begins, as many Gold Rush stories do, in a bar.

Or at least, above one.

When I visited Placerville this past weekend, I checked into the Cary House Hotel — that brick-and-mortar relic of stagecoaches, whisky breath, scandalous whispers, and the stubborn endurance of frontier architecture. Mark Twain slept here. So did Lola Montez. The building is a palimpsest of the early West, a structure that has seen miners stagger through its doorways and ladies of the evening glide down its staircases.

I approached the front desk expecting the usual check-in pleasantries. Instead, I found the first thread of a story we rarely pull.

Her name was Clarisa (I hope I’ve spelled it right), a young woman with the kind of calm Placerville confidence you only get by being born into the bedrock of the place. We chatted the way travelers and locals sometimes do, finding the seams between curiosity and hospitality. And then she said it — off-hand, like it was nothing at all:

“I was born here. My family is Cornish. Descendants of the miners.”

I stopped mid-sentence.

The hallway, the old wallpaper, the ghosted remnants of the 1860s seemed to lean in.

“You’re Cornish?” I asked. “As in the Cornish miners? The Empire Mine Cornish?”

She nodded.

That was all I needed.

“I’ve been looking for someone to talk to about that,” I blurted out. “I was shocked — horrified — when I visited the Empire Mine and realized how the Cornish were treated. They were basically indentured. We never hear their story. I want to tell it.”

Clarisa nodded again, more slowly this time, with the quiet recognition of someone who has lived inside a truth history refuses to print.

A Hidden People in a Boomtown Story

California textbooks love to make the Gold Rush look like an equitable carnival of global fortune-seekers — Mexicans, Chinese, Germans, Frenchmen, Chileans, Australians, and Americans from every corner of the states. The Cornish, if they appear at all, are usually described as “skilled hard-rock miners,” then swiftly erased back into the tunnels.

But the real story is darker, and older.

The Cornish arrived not as gold-hungry adventurers but as workers — imported expertise. They were the world’s best at getting ore out of unforgiving stone, and California’s mine owners knew it. The state needed deep-mining specialists to keep their massive operations profitable, and the Cornish were already conditioned to do brutal underground work. Generations of them had mined the collapsing tin veins of Cornwall, which the British aristocracy had drained for centuries.

So they came — not for riches, but for wages.

Wages controlled, manipulated, and often withheld by mining companies who owned everything:

the housing, the stores, the equipment, even the air the men breathed underground.

If that sounds familiar, it should.

This was not chattel slavery. But it was also not freedom.

It was the architecture of industrial bondage — a capitalism so lopsided it might as well have been a cage.

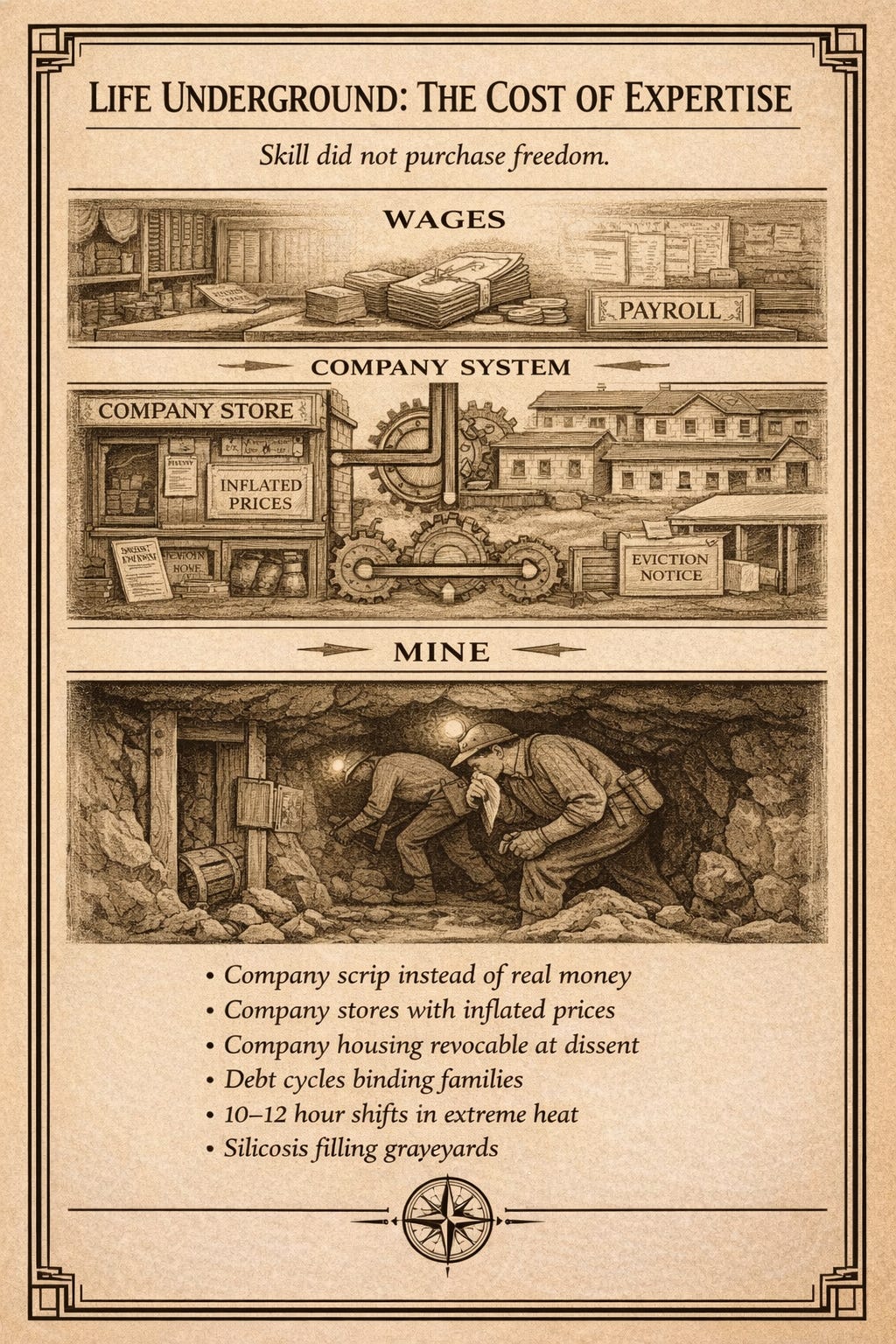

Life Underground: The Cost of Expertise

The Cornish were paid for their skill, yes, but they were paid within a system designed to keep them dependent:

Company scrip instead of real money.

Company stores where prices were inflated.

Company housing that could be revoked at any sign of dissent.

Debt cycles that kept entire families bound to the mines.

Dangerous shafts where men worked in temperatures over 100°F, for 10–12 hours at a time.

Silicosis, “miner’s consumption,” that filled the graveyards with men under fifty.

Their work built California’s fortunes.

Their names barely made it into the ledger.

And while the Gold Rush era is famous for saloons and brothels — the public-facing architecture of vice — the Cornish miners were rarely the ones filling those barstools or brothel rooms. Their wages didn’t stretch that far. Their lives were not the glamorous vice-soaked stories of gamblers and gunfighters. Their revelry was smaller, quieter, exhausted. Their evenings belonged not to dance halls but to survival.

If anything, they were the silent machinery beneath the barroom floorboards — the human engines powering the nightlife above them.

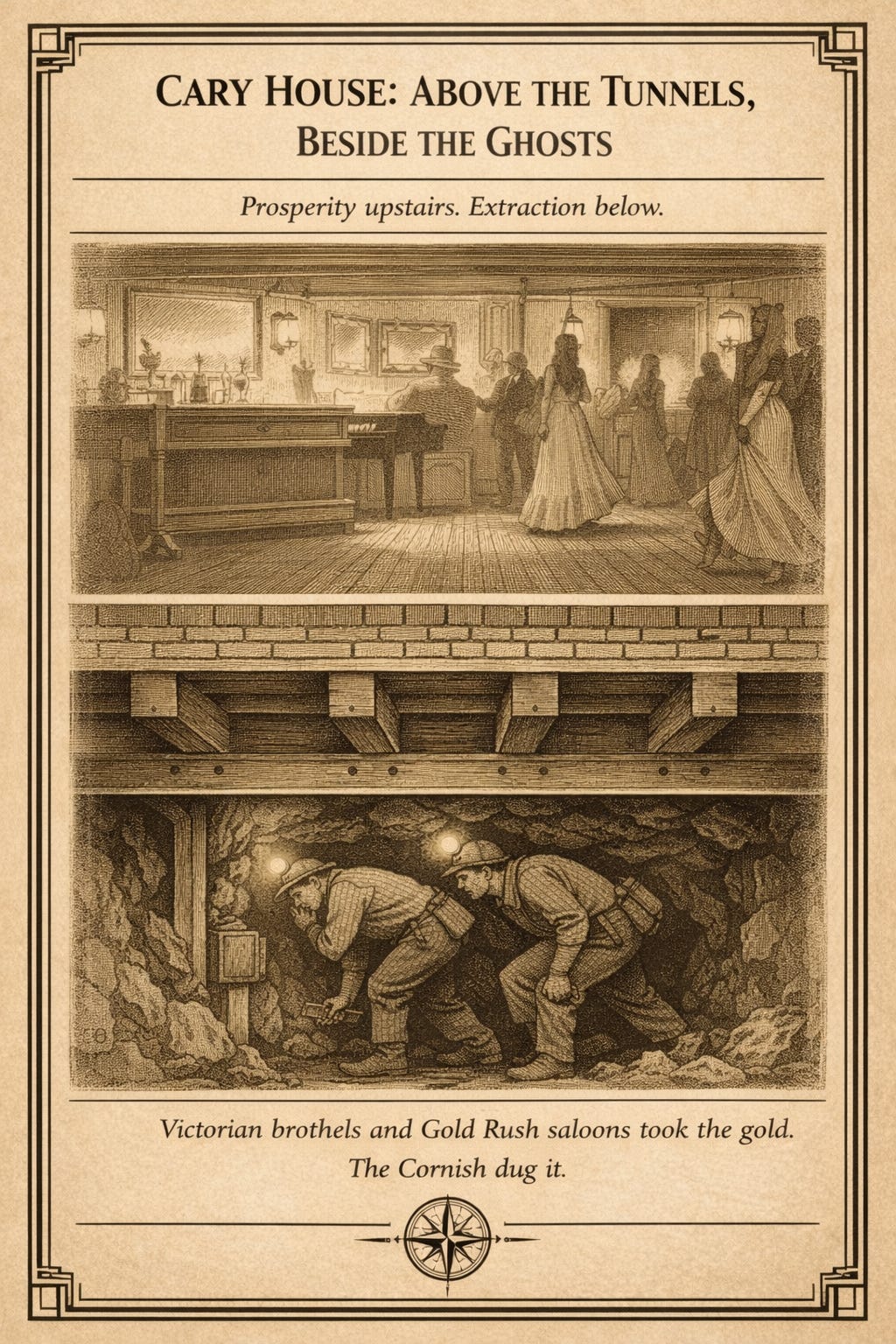

Cary House: Above the Tunnels, Beside the Ghosts

Standing in the Cary House, talking to Clarisa, I realized I was standing on the surface of a story buried so deep it had to be mined out. The hotel itself operated at the crossroads of two worlds:

Above ground: whiskey, laughter, piano music, the glint of gilt mirrors, boots on polished floors, women in silk moving like flickers of lanternlight.

Below ground: Cornish men descending into the earth, their hands leathered, lungs scorched, dreams small and pressed-flat.

Victorian brothels and Gold Rush saloons took the gold; the Cornish dug it.

The architecture tells you everything if you know how to read it.

The grand staircases, the thick brick walls, the imported chandeliers — all of them were built on the backs of underground laborers who seldom saw the inside of such opulence.

California’s early prosperity was an upstairs/downstairs world, but with a literal downstairs:

a vertical class divide carved into the mountain itself.

And up on that mountain, sitting at the front desk of a historic hotel, was a young woman quietly carrying the history of those men — men who lived and died without their story ever properly told.

Why Their Story Matters Now

The Cornish miners were not enslaved in the legal sense, but the mine owners engineered a system that trapped an entire ethnic group in cycles of risk, labor, and debt.

This matters because the Gold Rush is too often flattened into a romance — all gold pans and piano girls in red satin. But beneath the red satin was a workforce treated as disposable. And beneath the workforce were generations of Cornish families whose cultural memory is still shaped by that era.

Clarisa’s family is part of that memory.

So is Placerville.

So is every historic saloon and brothel in the Sierra foothills.

The bars tell the story of pleasure.

The brothels tell the story of survival.

But the mines tell the story of sacrifice — and the Cornish are the chapter we forgot to bind into the book.

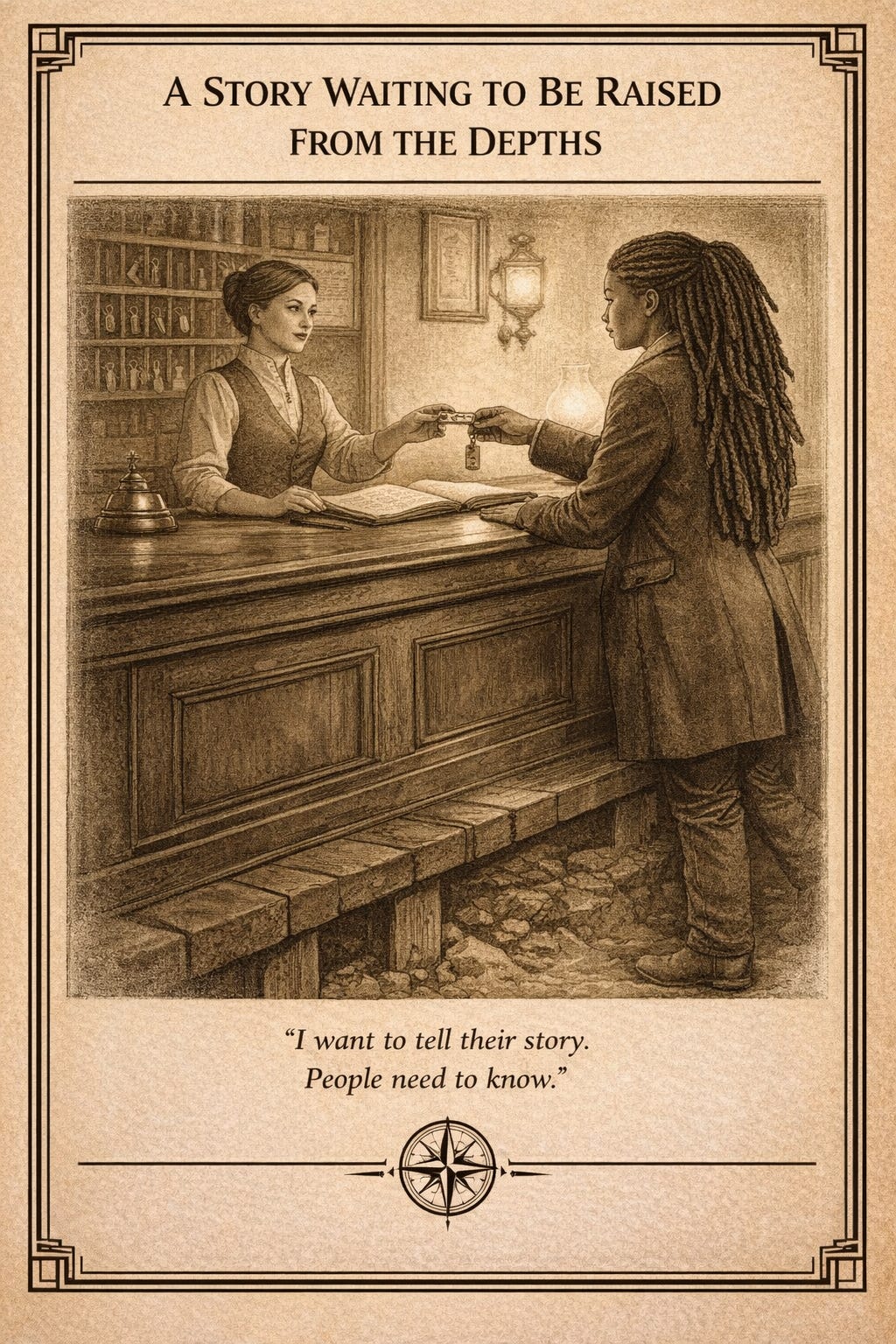

A Story Waiting to Be Raised From the Depths

As Clarisa handed me my room key, the conversation lingered in the air between us — a modern descendant and an accidental historian meeting at the threshold of a forgotten past.

I told her, with all the sincerity that moment deserved:

“I want to tell their story. People need to know.”

And she smiled the kind of smile that says she already knew that too.

Because every mining town has ghosts.

But it also has descendants.

And sometimes, if you’re lucky, the descendants are standing right at the front desk waiting to hand you the next chapter.

Thank you! Love learning some of the history we weren’t taught in school.

Good stuff Kimberly!

Sorry tuning in late — you’ve been busy! What an awesome gazette!

Talk soon.