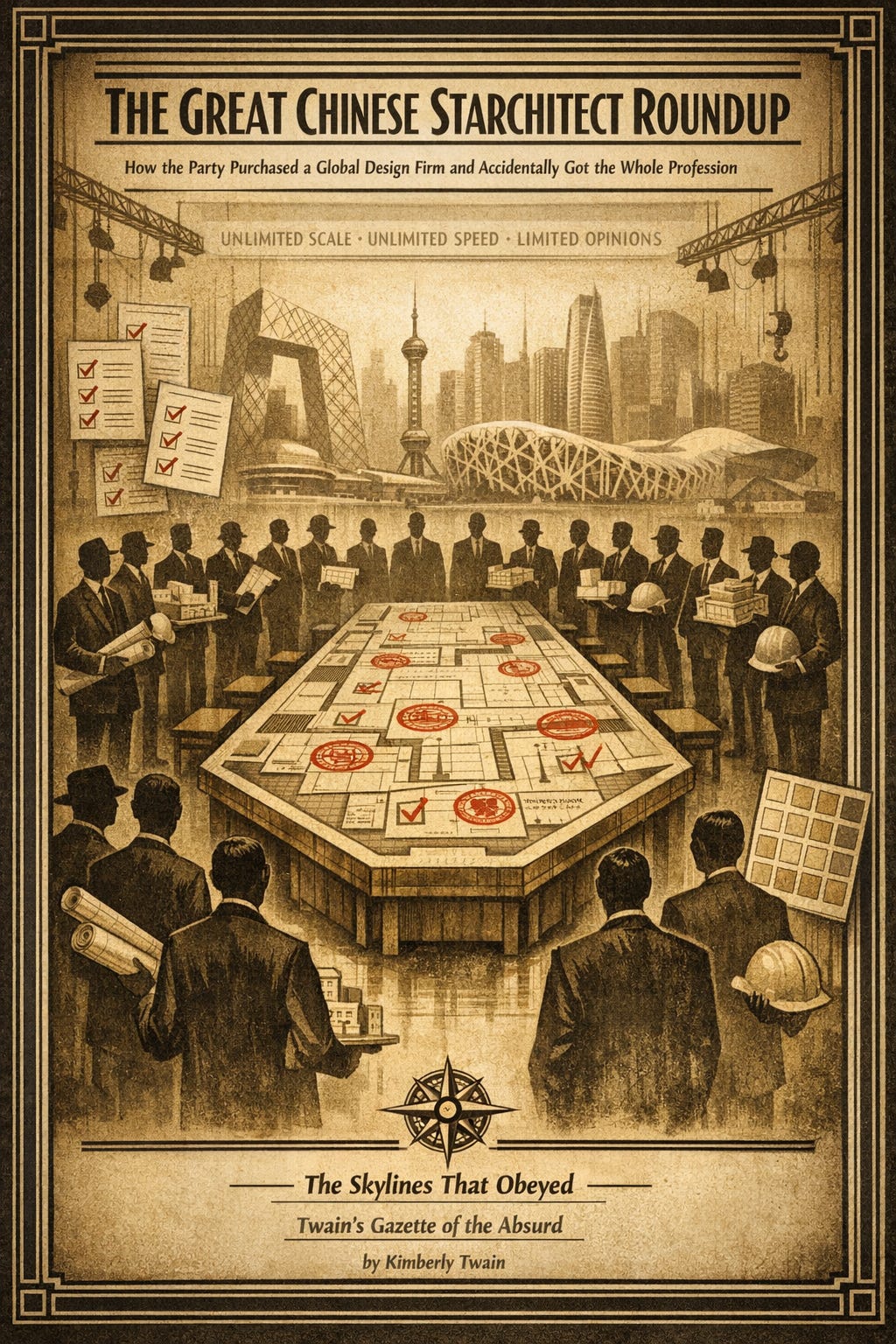

THE GREAT CHINESE STARCHITECT ROUNDUP - Part I

or, How the Party Purchased a Global Design Firm and Accidentally Got the Whole Profession

If you ever want to watch a grown architect weep, tell them you’ve landed a commission that is:

(1) unlimited budget,

(2) unlimited scale,

(3) unlimited speed, and

(4) entirely controlled by a government that does not tolerate witnesses, criticism, or the wrong shade of beige on a cladding mock-up.

They will pack their bags before you finish the sentence.

Thus begins the tale of how the Chinese Communist Party discovered the architectural profession’s greatest weakness:

moral flexibility in the presence of a large check.

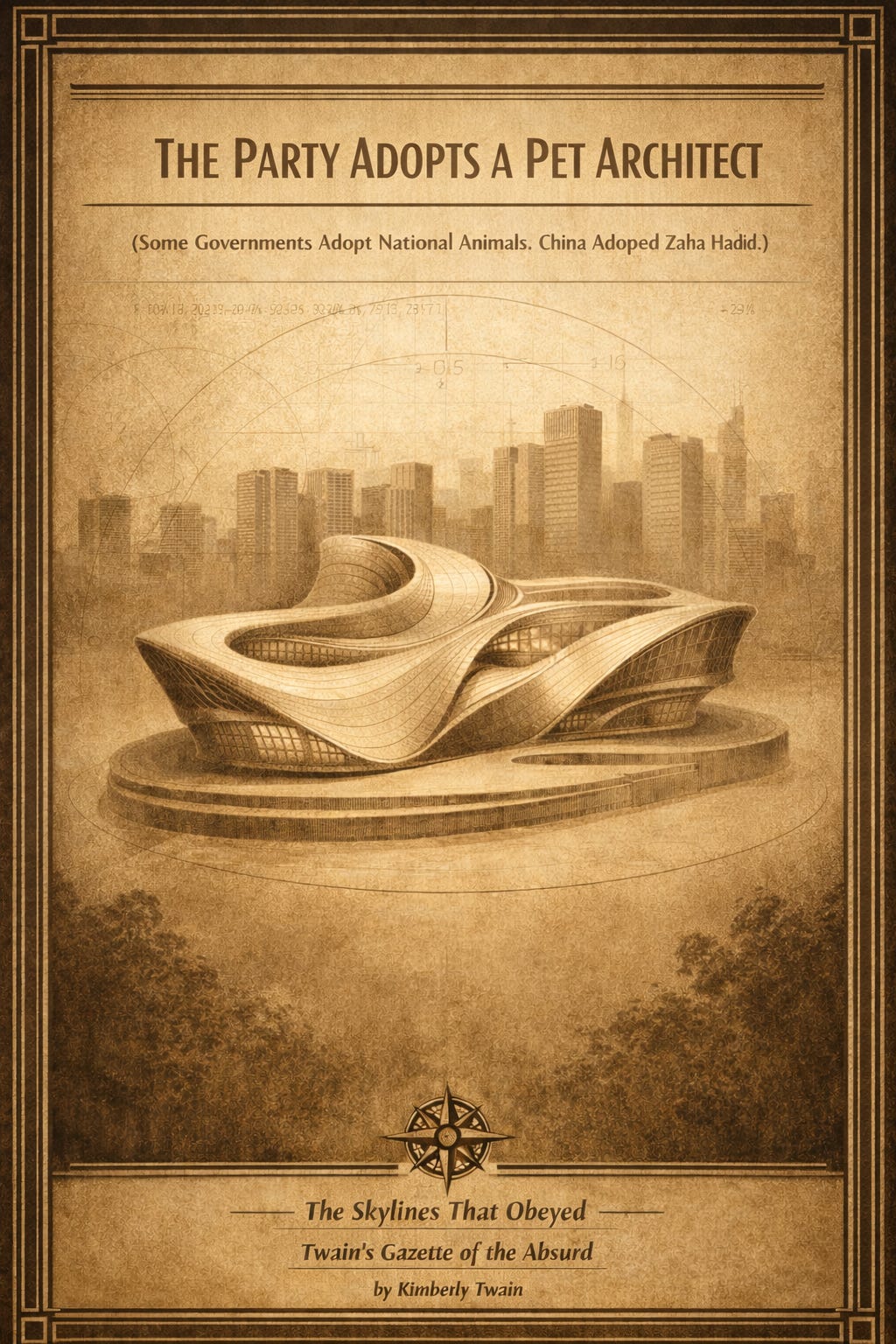

I. The Party Discovers Its New Favorite Pet: The Starchitect

Some governments adopt national animals.

China adopted Zaha Hadid.

There she is, parametric queen of curvature, bending Guangzhou like a gymnast with an unlimited yoga budget. The Party adored her. Never had authoritarianism looked so fluid. So feminine. So Instagrammable.

Suddenly every Politburo meeting included the phrase,

“Get me a Zaha curve, but make it patriotic.”

And Zaha delivered, blissfully unaware that she’d become the unofficial Minister of Futurist Appearances.

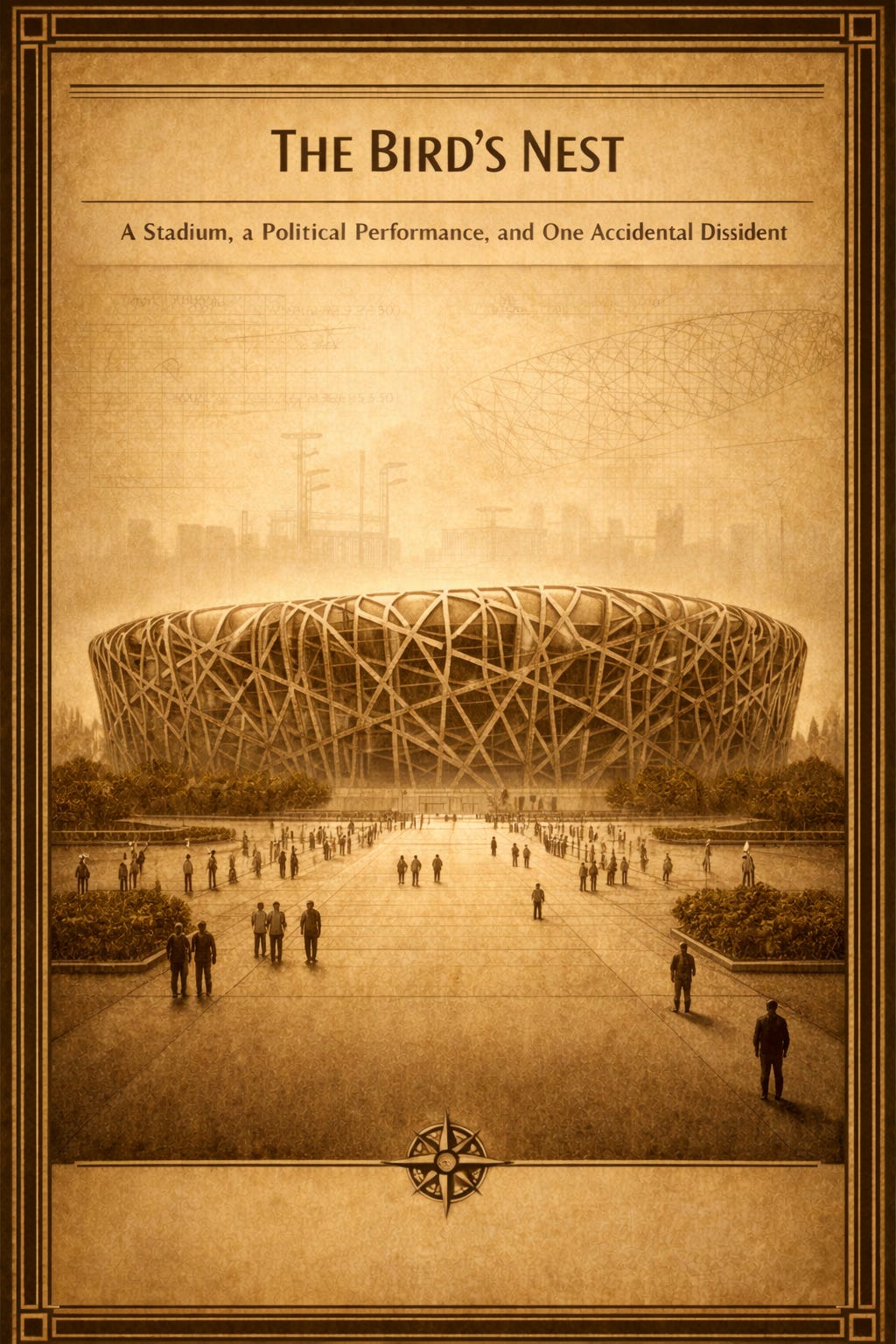

II. The Bird’s Nest: A Stadium, a Political Performance, and One Accidental Dissident

Enter Herzog & de Meuron and their sidekick Ai Weiwei, who at the time was still allowed to leave his house.

They built a stadium that looked like a basket for holding the world’s largest propaganda egg. Newspapers raved. Journalists swooned. The Party glowed with pride.

Then Ai Weiwei opened his mouth.

You have not truly lived until you’ve seen a regime beam with joy at a building and simultaneously try to erase the man who helped design it.

The Bird’s Nest stands today as a monument to the enduring power of architectural form over human freedom.

(That and the power of a really good PR team.)

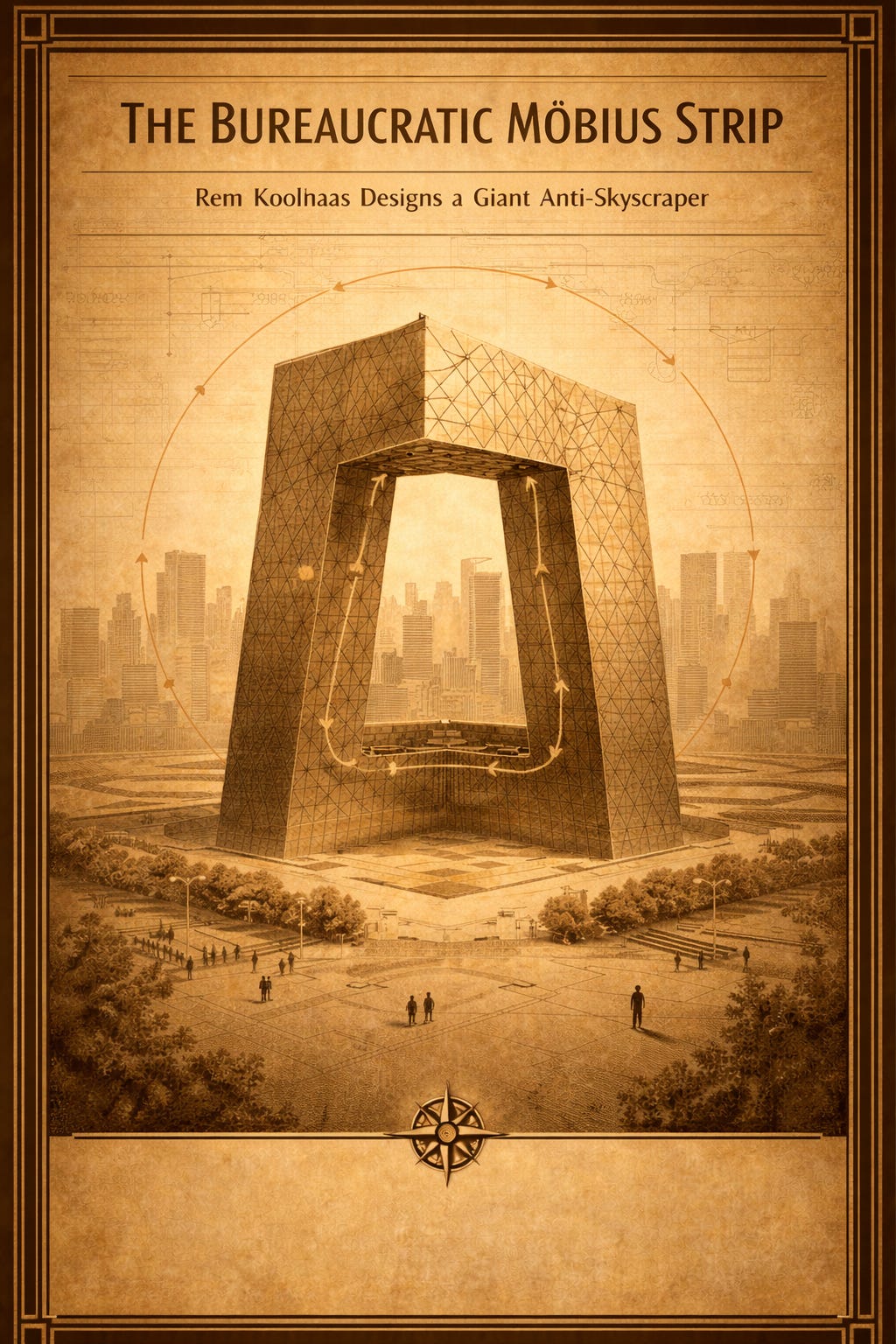

III. Rem Koolhaas Designs a Giant Bureaucratic Möbius Strip

Rem Koolhaas looked at Beijing and decided what it really needed was a building that physically embodied the experience of watching state television:

confusing, continuous, and structurally questionable.

And thus the CCTV Headquarters was born: the world’s first anti-skyscraper skyscraper, bending in on itself the way free thought does inside a surveillance jurisdiction.

Architectural critics called it “bold.”

Citizens called it “Big Pants.”

The Party called it “modernization.”

Everyone left the conversation pleased, which is how you know something is very wrong.

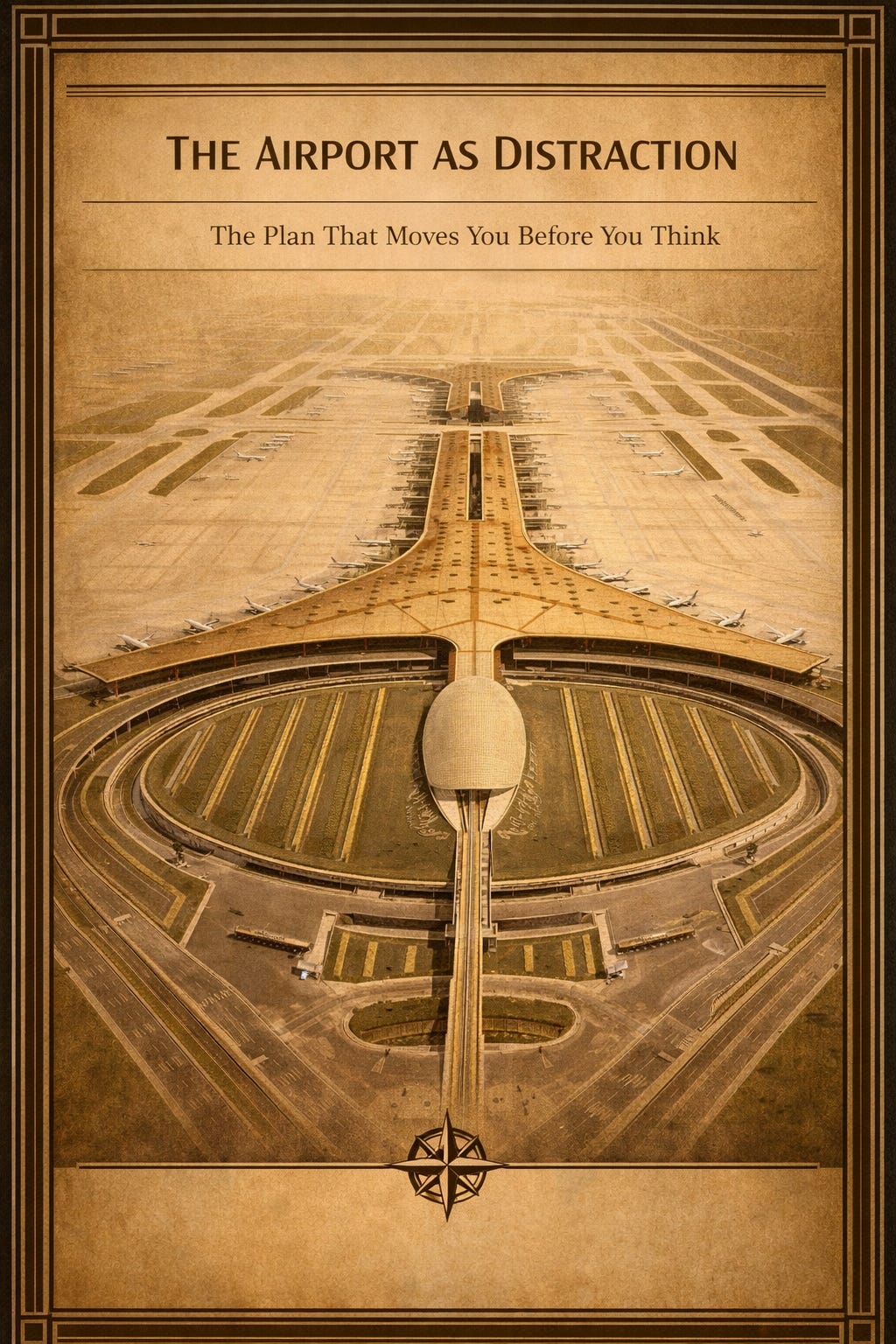

IV. Foster Arrives, Builds an Airport So Nice It Almost Distracts from Reality

Sir Norman Foster—knight of the British realm, lord of the high-tech cantilever—constructed an airport so vast it could hold the GDP of a small nation and still have room for duty-free.

Beijing Capital Terminal 3 is the architectural equivalent of being welcomed to a fancy dinner by a host who has politely concealed all the knives.

Travelers admire the sweeping roof, the amber glow, the effortless circulation.

They rarely notice the cameras.

Good architecture works in mysterious ways.

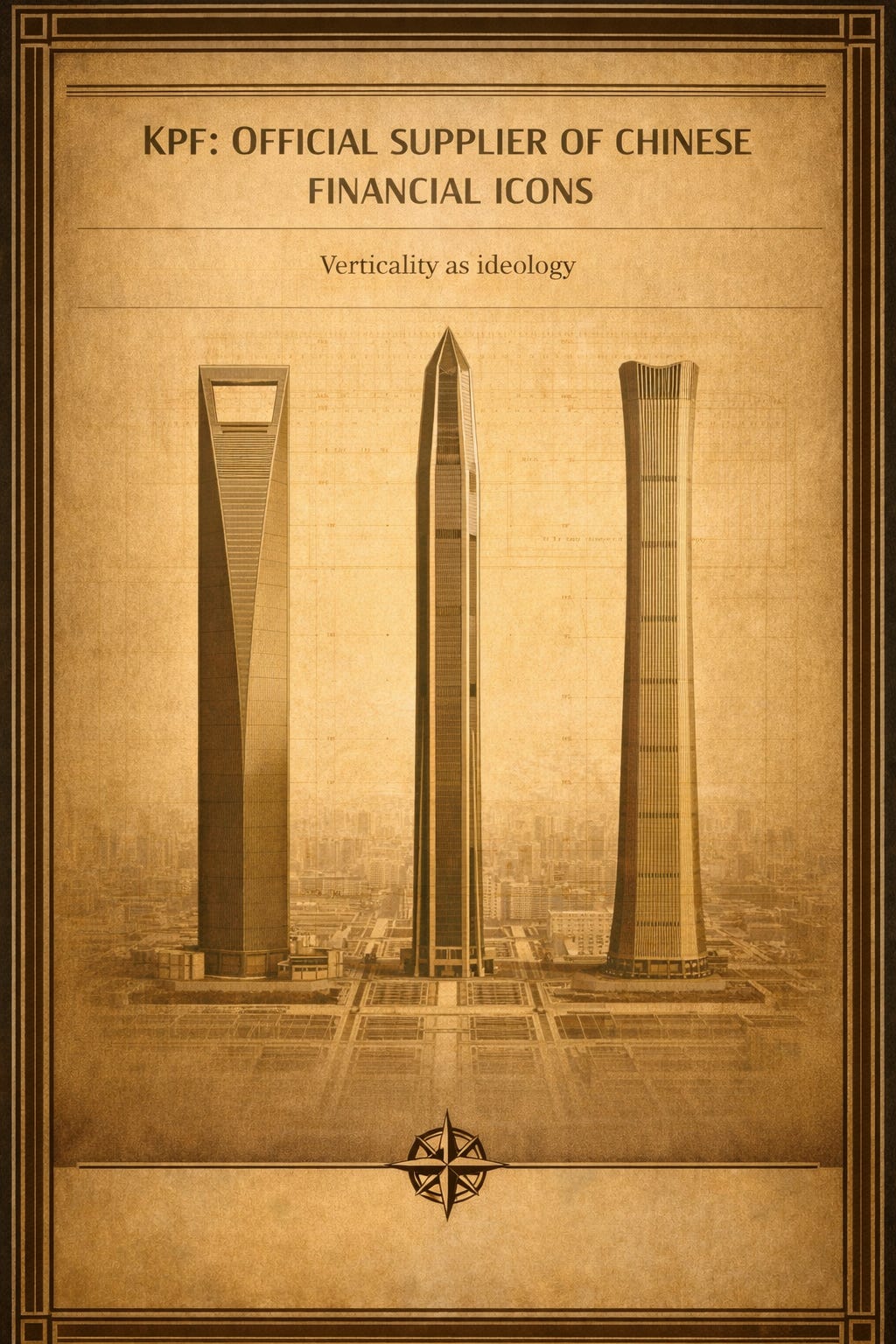

V. KPF: The Official Supplier of Chinese Financial-Phallic Icons

Every time China needed to announce, “We too have capitalism, but with Chinese characteristics,” KPF produced another vertical exclamation point.

Shanghai World Financial Center: The Bottle Opener of Global Ambition.

Ping An Finance Center: The Razor Blade of Technocratic Discipline.

China Zun: The Ceremonial Wine Vessel of Authoritarian Confidence.

These towers say:

“We may not allow unrestricted markets, but we absolutely allow unrestricted height.”

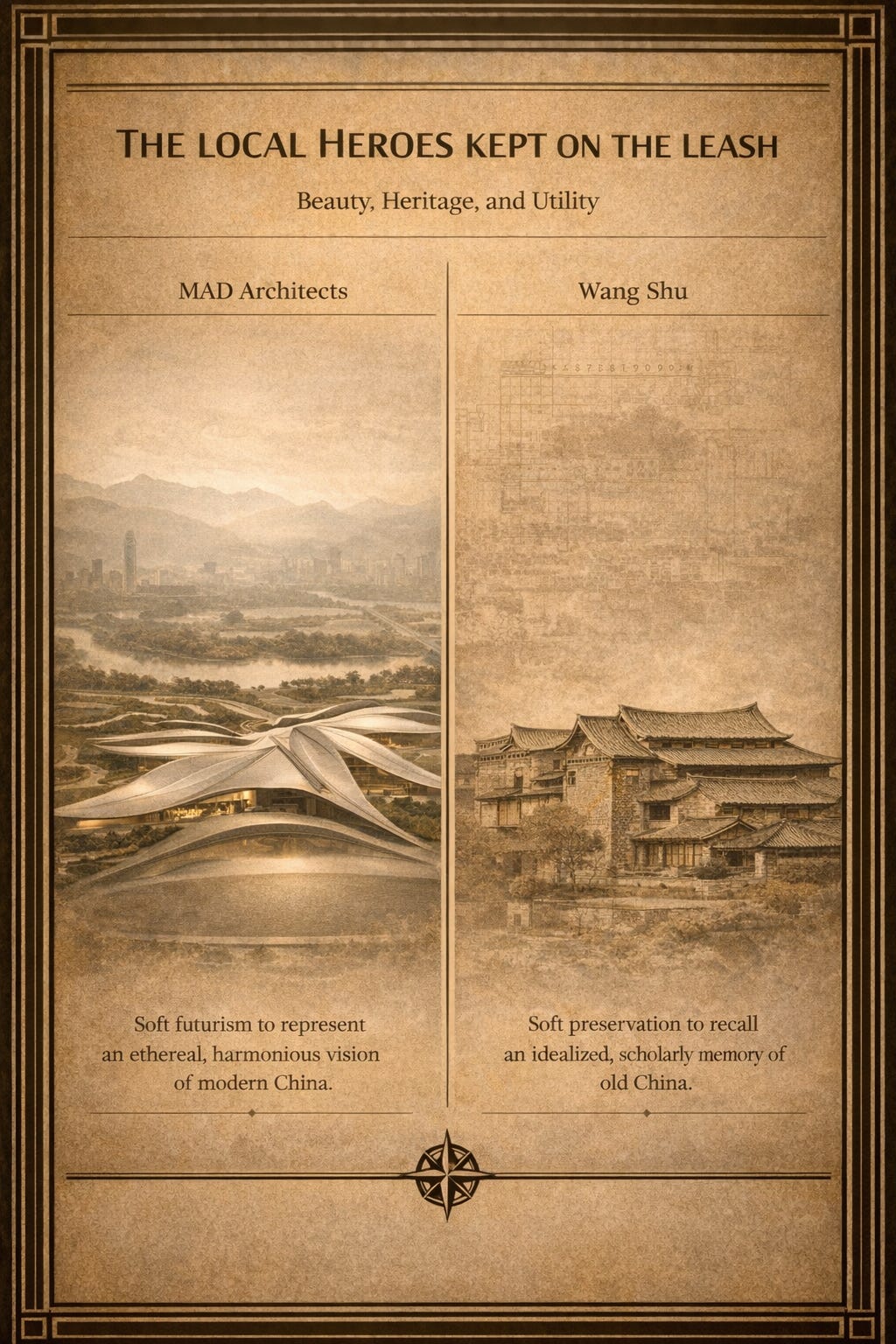

VI. The Local Heroes the Party Keeps on the Leash

MAD Architects

Beautiful, organic, mist-kissed futurism designed to evoke mountains, clouds, and philosophical harmony.

The Party loves this.

A soft totalitarianism needs soft curves.

Wang Shu

The scholar-architect of salvaged tiles and folk wisdom.

International critics call him a preservationist saint.

The Party calls him useful.

While entire historic districts disappear overnight, Wang Shu’s campus projects politely reassure the world that China treasures its heritage—just not enough to stop demolishing it.

VII. Why Architects Keep Going Back

Because China offers architects three things they can no longer get at home:

A blank slate (even if something was already on it).

A budget (even if it doesn’t technically exist yet).

The ability to build something ridiculous without a neighborhood association staging a protest outside your hotel room.

Western democracies have zoning boards.

China has political directives.

Architects know which one gets a tower built faster.

VIII. Moral Clarity Arrives Late and Leaves Early

Eventually, some architects realize what they’ve enabled.

Usually after the project is completed, photographed, reviewed, award-submitted, monetized, and added to their monograph.

Rem occasionally frowns in an interview.

Zaha (were she still here) would issue a cryptic, elegant shrug.

Herzog & de Meuron pretend they didn’t notice the political implications.

Ai Weiwei posts something devastating and true on Instagram.

But the buildings remain.

Architecture is the perfect accomplice:

silent, tall, photogenic, and incapable of testifying.

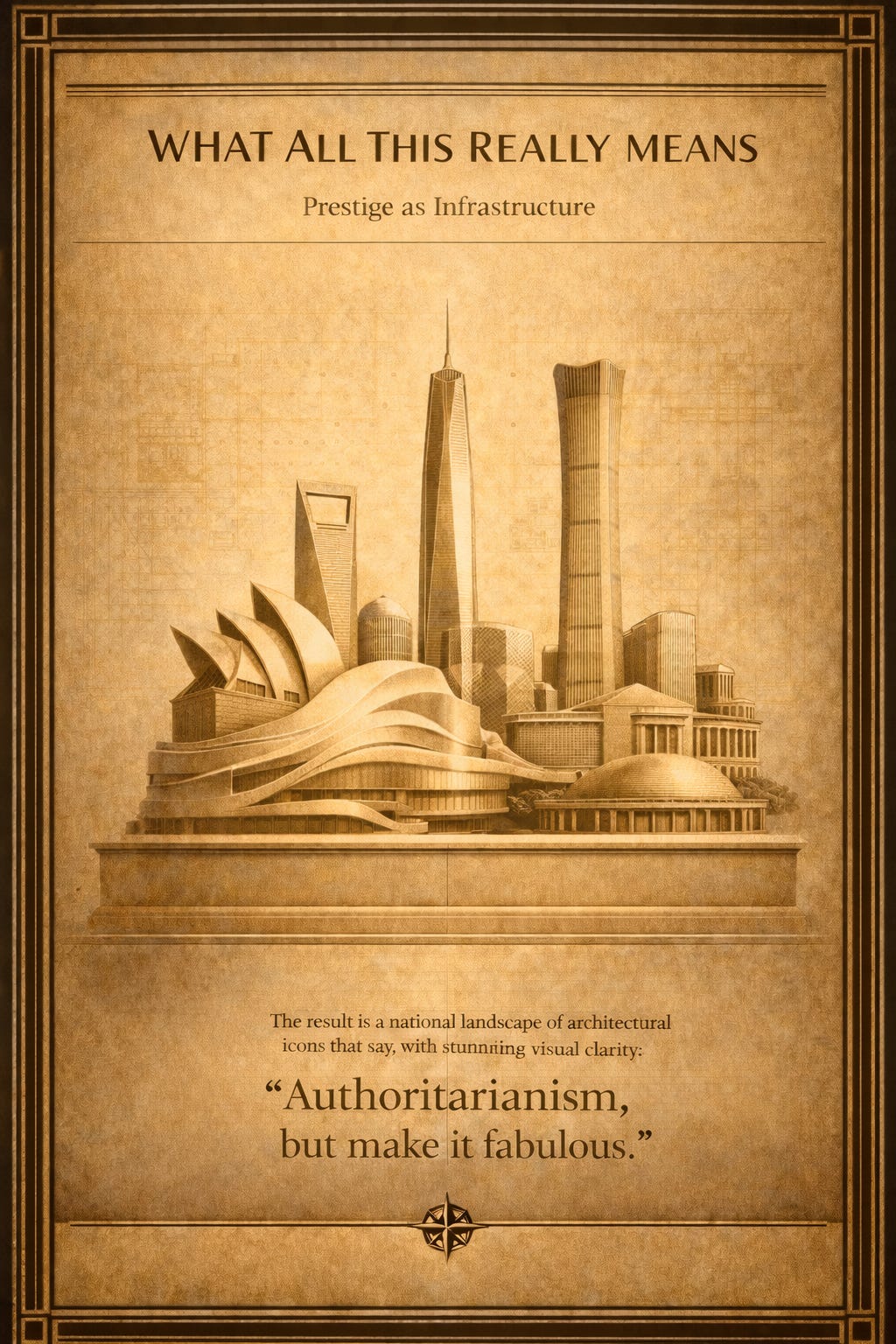

IX. What All This Really Means

China didn’t just import architects.

It imported aesthetic cover, cultural endorsement, and the soft glow of global prestige.

And the starchitects?

They got to build the things democracy would never permit.

It is a mutually beneficial relationship wrapped in titanium panels, press releases, and the occasional ethical hangover.

The result is a national landscape of architectural icons that say, with stunning visual clarity:

“Authoritarianism,

but make it fabulous.

Author’s Note for Architects

The architectural renderings and plates in this series are conceptual interpretations based on real, built projects.

They are intentionally stylized, compressed, and editorialized to serve argument, metaphor, and critique.

These images are not technical drawings, construction documents, or literal reproductions.

They preserve recognizable form, massing, proportion, and spatial logic, while exaggerating posture, context, and symbolism to make political and cultural structures legible.

Readers — especially architects — are strongly encouraged to look at the actual buildings themselves.

Many of them are genuinely extraordinary works of design, engineering, and craft, and deserve to be seen on their own terms.

In other words:

the buildings are real,

the critique is real,

the drawings are doing editorial work.

Architects will recognize the sources.

They are meant to.

— Kimberly Twain

One of your best articles to date. Bravo!

The architecture profession has been a willing accomplice not asking any awkward questions.